A popular picture book of the 1980s, Peepo! And what do Virginia Woolf’s unfinished wartime memoirs have in common? As it turns out, more than a little.

Sketches of the Past is a memoir of Woolf’s childhood, written as a break from her work on a biography of the art critic Roger Fry during the beginning of the Second World War. In a section dated 8 June 1940, Wolf writes that “the battle is at its peril; Every night the Germans fly over England; It comes closer to this house every day”.

In the cask! The Battle Has Come to Home, by Janet and Alan Ahlberg (1981). The father wears army uniform, a gas mask hangs from the bedpost and a framed photograph of Winston Churchill hangs on the wall.

Outside, an air raid warden passes by, while planes and barrage balloons fly overhead. According to Alan Ahlberg, born in 1938, the book is also a memoir: “I am Pipo! Child”. Pipo! therefore connects the form of the sketch – a piece of life-writing – with its wartime context in a way that, to my knowledge, has never been explored.

For Woolf, a modernist writer concerned with internal perspective and subjective viewpoint, describing her childhood was both an opportunity and a challenge. His memories are of “many bright colors”; many distinctive sounds; Some humans, caricatures; humor; Many violent moments of happening, which always included a cycle of the scene he had cut”.

It describes the physical structure of Pipo with shocking accuracy! The alternative spread depicts the child on the left page and on the right is a circle depicting what he sees. When the circles are removed, Janet Ahlberg’s full-page portrait is visible, in Woolf’s words, “the scene she had cut out”.

Pipo! The Creation, which has enthralled generations of children, also provides surprising insight into the perspective through children’s eyes as Woolf saw it.

While trying to describe Kensington Gardens, Woolf found that, “I cannot get right, save by fitting the proportions of the outside world.” These gaps and deficits led him to conclude that “a child must have an inquisitive focus; It sees an air-ball or shell with extreme distinctness… but these points are surrounded by vast empty spaces.

Pipo! Baby shares this “curious focus” on the immediate details of his world. Moved to a park far less grand than Kensington Gardens:

He watches the tassels fly

on my grandmother’s shawl

and fringe on the pushchair

and his teddy

And his ball.

Yet when the circle is raised the “proportions of the outside world” are revealed, enabling double vision that combines the perspectives of both the child and the adult. This enables mature readers to recognize the danger posed by the Blitz, symbolized by barrage balloons and a ruined building overlooking the park, while the child naturally remains unaware.

first memories

One of the earliest memories recounted by Woolf in the sketch is of “being half asleep, half awake, in bed in the nursery at St. Ives.” It is to hear the waves breaking, one, two, one, two,… behind a yellow curtain… it is to lie and hear this splash and see this light, and feel. ..the purest ecstasy I can imagine.”

In Peepo!, the words “one, two, three” recall Woolf’s description of waves, while the child’s first impression – the book’s “first memory” – includes:

shadows are moving

on the bedroom wall

and the sun on the window

Both authors vividly describe what the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan called the “imaginary”, a state before language acquisition in which the child is not yet aware of himself as an autonomous being. As Wolf says: “All I deserve is a feeling of ecstasy.”

What makes the sketch so poignant is that Wolf’s ecstasy will not last. She describes feelings of “guilt” and “shame” associated with the mirror in the hallway of her childhood home.

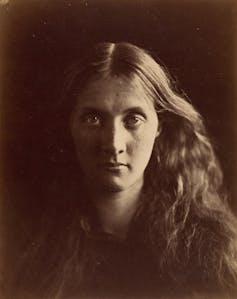

Woolf connects this to “another memory, also Hall’s”, of being molested by her half-brother Gerald Duckworth, 11 years her senior. And this lesson came to a halt with the death of her mother, Julia Stephan, in 1895, when Woolf was 13. For Woolf, her mother was integral to “the life of the family”, meaning that “after that day there was nothing left of her”.

In Pipo!, by contrast, “The landing mirror / With its iridescent rim” contains a vision of perfection, depicting “a mother with a child / Just like her”. This also cannot last: the child stands on the threshold of Lacan’s “mirror stage”, where he will recognize his reflection, understand that he is distinct from the mother, and begin to enter the realm of language.

Still Pipo! Ending with the child “falling fast asleep and dreaming”. The family is intact, the bombs have not yet fallen – and Wolf’s childhood joy is restored.![]()

,Author: Bethany Layne, Senior Lecturer in English Literature, De Montfort University)

,disclosure statement: Bethany Layne does not work for, consult, hold shares in, or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and she has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond her academic appointment. haven’t done)

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.