Hyderabad researchers turn stethoscope into a device that can help people speak

Researchers at IIIT-Hyderabad have developed a silent speech interface that converts non-audible babbling into vocal speech, helping people with speech impairments.

A team of researchers from the International Institute of Information Technology (IIIT) Hyderabad has developed an innovative Silent Speech Interface (SSI) that can convert non-audible babbling into vocal speech.

This groundbreaking technology has the potential to improve communication for people with speech disabilities.

The research team, led by TCS researcher and PhD student Neel Shah along with Neha Sahipjohn and Vishal Tambrahalli, worked under the guidance of Dr. Ramanathan Subramaniam and Professor Vineet Gandhi.

Their findings are published in a paper titled “Stethospeech: Speech Generation through a Clinical Stethoscope Attached to the Skin,” which was presented at the UbiComp/ISWC conference in Melbourne, Australia.

What is Silent Speech Interface (SSI)?

Silent Speech Interface (SSI) is a form of communication where no sound is produced audibly. “The most common form of SSI is lip reading, but there are also other techniques such as ultrasound tongue imaging, real-time MRI, and electromagnetic articulography. However, these methods can be highly invasive and do not work realistically,” explains Neel Shah. – Time.”

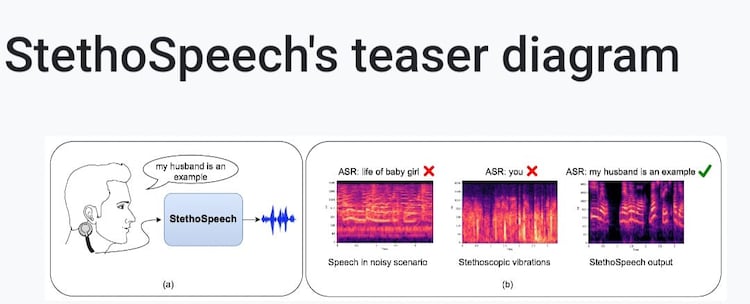

To address these challenges, the IIITH team used a behind-the-ear stethoscope to capture non-audible murmurs (NAMs) and convert them into understandable speech.

“We wanted to create a solution for people with voice disorders that could help them engage in social interactions more easily,” Professor Gandhi said.

How does this work?

The team collected NAM vibrations from people babbling text, which they labeled the “stethotext corpus”.

These vibrations were recorded in a variety of environments, ranging from everyday office settings to noisy venues such as concerts. Using this data, they trained a model to convert vibrations into speech.

“We captured the vibrations when people were babbling text and then trained the model to convert these vibrations into vocal speech,” Professor Gandhi said.

What sets this research apart is its simplicity. Instead of complex equipment, the team used a simple stethoscope to transmit NAM vibrations to a mobile phone via Bluetooth. The phone then converts the vibrations into clear speech in real time.

Unique features of innovation

An extraordinary feature of this system is its ability to work even for users who were not part of the original training.

Neel Shah said, “We showed that even in a ‘zero-shot’ setting, where the model has never encountered the speaker before, the system can still accurately deliver speech.”

Additionally, the system can convert vibrations to text almost instantly, making it practical for use in the real world, even if the person is walking.

Another unique aspect is the ability to customize the voice output. Users can choose various speech characteristics such as gender or accent, for example, South Indian English accent.

“We can even create personalized models for users with just four hours of recorded murmur data,” Professor Gandhi said.

The team’s work is part of a larger effort to make communication more accessible to people who cannot speak.

Previously, he worked on converting lip movements into speech using a text-to-speech (TTS) model. “Our model mimics how humans learn to speak by interacting with sounds before they learn to read,” Professor Gandhi said.

This method allows them to create highly accurate systems that can enable any speaker to communicate in any language.

one step forward

Wireless stethoscope systems have other applications besides helping people with speech disabilities. It can be used in extremely noisy environments, such as rock concerts, where normal speech is difficult to hear.

Researchers see the potential for discreet communication in professions such as security services, where whispering is often used.

Professor Gandhi said, “This technology is a game-changer because previous studies assumed that clean speech data was always available for training. But for individuals with speech disabilities, we do not have that facility.”

The team is now looking for collaborations with hospitals to test their system on patients.

Looking to the future, the researchers are excited about the potential impact of their work. “It’s amazing to think that we can give a voice to someone who has lost someone,” Professor Gandhi said.

With further testing and collaboration, the IIITH team’s innovation may provide new hope for people with speech disorders, increasing their ability to communicate fluently in a variety of settings.