Sam Altman-backed startup eyes first gene-edited baby, as scientists warn it’s dangerous

Silicon Valley billionaires love to pursue extreme health tech. His next passion, after dabbling in anti-aging technology, is making designer babies possible by editing genes.

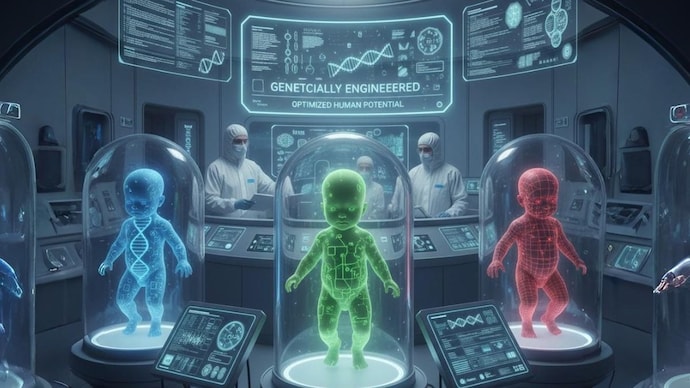

A secret project is quietly taking shape in Silicon Valley, led by OpenAI boss Sam Altman and his husband Oliver Mulherin. A gay couple has spent millions backing a startup that is working on technology that could one day allow parents to have gene-edited children free of inherited genetic disorders. As extraordinary as this technology sounds, the idea of having a genetically engineered child is not only controversial, but is considered illegal and highly unethical in many parts of the world. Yet billionaires are investing in this technology anyway, and now the scientific community is worried.

Sam Altman and Oliver Mulherin, along with Coinbase co-founder and CEO Brian Armstrong, are some of the high-influencers in Silicon Valley who are backing biotech startup Preventive, according to a report from the Wall Street Journal. This startup’s mission is to create technology that can help scientists rewrite the genetic blueprint of an embryo so that future children never have serious genetic disorders.

Supporters of this idea see it as a breakthrough technology that could finally break the chain of diseases that have been passed down for generations. But critics argue that, even if this approach sounds good, the company is venturing into territory that remains scientifically risky, ethically risky and potentially socially explosive.

What exactly are genetically engineered babies?

To understand why this technology is causing such a stir, it helps to first understand what genetically engineered babies actually are. In simple words, before a child is born, they contain the DNA of their parents. Genetic diseases are passed on through this DNA, and most such conditions are not treatable with current medical technology. Gene-editing, as the name suggests, aims to alter an embryo’s DNA and remove faulty sections – often using tools like CRISPR – so that the genes are fixed before the baby is born. Theoretically, this means they can grow up without the diseases that have long plagued their families.

But the reality of gene-editing is far from simple. Editing embryos involves making permanent changes that are passed on to future generations, meaning that any mistake, no matter how small, could impact the future in ways that scientists still can’t predict. There are many other areas where this technology can be misused.

Critics also argue that genetic editing could deepen existing social divisions. If only rich people could produce healthy or strong children, society could become divided along biological lines. An even deeper fear is the slide towards so-called “designer babies”, where parents begin to select for qualities such as intelligence, height or appearance. Many experts argue that once that door is open, it will be almost impossible to close it.

That is why many researchers call this technology both promising and extremely dangerous. And after the world was shocked by the first gene-edited babies born in China in 2018, global regulators tightened their stance. Most countries now either heavily restrict or completely ban embryo editing for pregnancy. Scientific regulators have repeatedly warned that the technology is nowhere near safe for use in the real world. They point out that even small genetic edits can introduce unknown side effects, and long-term consequences may take decades to emerge.

Why is Sam Altman’s startup working on gene-editing?

Startup Preventive believes that responsible progress is possible with this technology. The company argues that rather than watching families suffer from inherited diseases from generation to generation, science should intervene at the earliest – and most effective – point. And that is why many big names in Silicon Valley are investing money in this idea, that too at a time when the technology is being heavily criticized.

For now, Preventive emphasizes that its focus is solely on preventing disease, not enhancing human qualities. Proponents say strong regulation and transparent oversight can keep the technology based on medical need. But even those who believe in the potential of embryo editing acknowledge that this technology is ethically complex territory, and that doing so without a clear roadmap would be risky.